Learn the complete, step-by-step process of writing a marketable Hollywood screenplay from successful, working writers.

Learn to write a script Hollywood will want to produce

Every great movie is made from a great script. It doesn’t matter how big the budget gets, how authentic the actors perform, or how magnificent the visual effects appear unless the screenplay is engaging, dynamic, and believable. Films with high production values have been known to flop because the scripts couldn’t handle the weight of their own plots, structures or even main characters. Rarely has a bad script been made into a good movie. Writing a script is a craft that takes time to learn and a tremendous amount of discipline, and it also requires understanding story structure, psychology, human dynamics, and pacing.

In the FilmSkills Screenwriting Course, you will learn the step-by-step process of writing a script from top Hollywood writers. From the very beginning stages of developing a marketable idea, creating dynamic characters, understanding story structure, and finally learning how to market your script. You will gain all the tools you need to write a professional Hollywood screenplay.

FilmSkills takes a real world approach to screenwriting by blending the art with the business. A great script does no good if it’s sitting on your desk, so we help you write a script producers will want to make.

I’ve read so many screenwriting books, and nothing comes close to the depth and quality of the FilmSkills Screenwriting Course. – Bill R.

Lessons in the Screenwriting master Class | |

|---|---|

| Developing the IdeaStrong ideas are the basis of a compelling story, if they are fleshed out the right way and appeal to a mass audience. In this module, we’ll show you where you can look for creative, original ideas and how to determine their marketability with both studios and producers. |

Story StructureStories have been told a particular way throughout human history, and movies are no different. Both the audience and filmmakers have agreed upon an unspoken structure for how the plot points in a movie are revealed. In this module, we’re not only going to expose this underlying structure, but teach you how to incorporate it into your production. | |

The Three Act StructureIn this module, we’ll show you how to use the three act structure to properly pace your story, what should occur in each act, the length of each act, what happens at the beginning, middle and end of each act, and how to apply these techniques to your story. | |

| A-Story and SubplotsIf you were to describe a movie in a few sentences, you would probably give me a great summary of the main plot of the story- “Raiders of the Lost Arc is about an archaeologist who goes in search of the Arc of the Covenant.” Or “Twilight” is about girl torn between two men – a vampire and a werewolf.” In both of these examples, you would be correct – but what you told me was what is part of what’s called the “A” plot, or the main storyline of the movie. Movies can also include several smaller stories called subplots, which help reveal character, push the story forward and ultimately support the A-plot. In this module, we’re going to look at how to effectively write both the A-plot and the subplots. |

Story PacingA good screenplay takes the audience on an emotional roller coaster, and one of the challenges facing each writer is how to keep the audience engaged through each and every minute of the story. In this module, learn literary techniques for maintaining strong pacing – especially through the second act. | |

| The ProtagonistAs you’re writing your screenplay, the most important character to write is the protagonist. But you have several choices – is he also the main character? Does the protagonist change or remain steadfast? How do you write a character the audience will care about? How can flaws help the protagonist solve the story problem? Knowing the answers to these question will help you craft a compelling character, so in this module, we’re going to explore techniques for writing a strong, multi-dimensional protagonist. |

| The AntagonistThe antagonist has been classically referred to as the bad guy, the villain, or the adversary. But more properly defined, he, she or it is the literary opposite of the protagonist – the character who opposes the goals of the protagonist. In this module, we’re going to explore techniques for writing a strong antagonist, how to make him, her or it a real, multidimensional character. |

| Conflict TypesConflict in a story is everything – it defines the very purpose of the protagonist. We can divide the types of conflict into one of several categories – each category helping to define the antagonist’s role in the story. They are man vs. man, man vs. self, man vs. society, man vs. nature and man vs. the supernatural. So in this module, we’re going to explore these various types of conflict and how you can use them to craft a compelling antagonist. |

| Supporting CharactersA movie is populated with dozens of other characters – many of whom have an influence on the protagonist and the antagonist. These supporting characters either help or hinder, compliment or compete with our protagonist and antagonist. They add vibrancy and excitement to the story, all while serving as a valuable literary tool for you as you write the screenplay. In this module, we’re going to explore the function of supporting characters. |

| Character ArchetypesAll characters can be broken down into eight different archetypes – now these are the basic ingredients of creating a character, so of course you can mix and match them to create more complex, unique characters. But every supporting character fulfills one of more of these roles. The eight archetypes are the protagonist and the antagonist, Reason, Emotion, The Sidekick, The Skeptic, the Guardian and the Contagonist. So, in this module, we’re going to explore the six archetypes that make up supporting characters. |

| Personality and BackstoryThe act of writing is much more than simply creating characters – it’s about writing real people with real fears, ambitions, strengths and weaknesses. But although you need to be able to create real, believable people, every choice you make when creating them needs to support the story. Who they are helps them confront the plot, learn more about themselves and ultimately succeed or fail. Their background gives them the tools and experienced they need to confront the conflict, and most importantly, their tragic flaw gives their story a personal arc. So, in this module, we’re going to discuss how to create personality and backstory. |

| Dialogue and SubtextOne of producers’ biggest criticisms of a script is the weak, cliche dialogue. Learn how to make your script stand out with tight, engaging dialogue from working Hollywood experts. Emmy-winning Executive Producer of “Everybody Loves Raymond,” Steve Skrovan, Writer/Producer Mike Emanuel, Writer John Anderson, Writer/Script Doctor David Freeman and Emmy-winning Director Jason Tomaric share valuable insight into avoiding cliches and writing tight dialogue. |

| From Title to OutlineThe treatment and outline for a movie is literally the backbone of the story, and the quality of your work in this phase can either make or break your script. Learn how to write an effective treatment and outline and simplify the process of writing the first draft. Working Hollywood writers teach you how to get the most out of this valuable writing tool. |

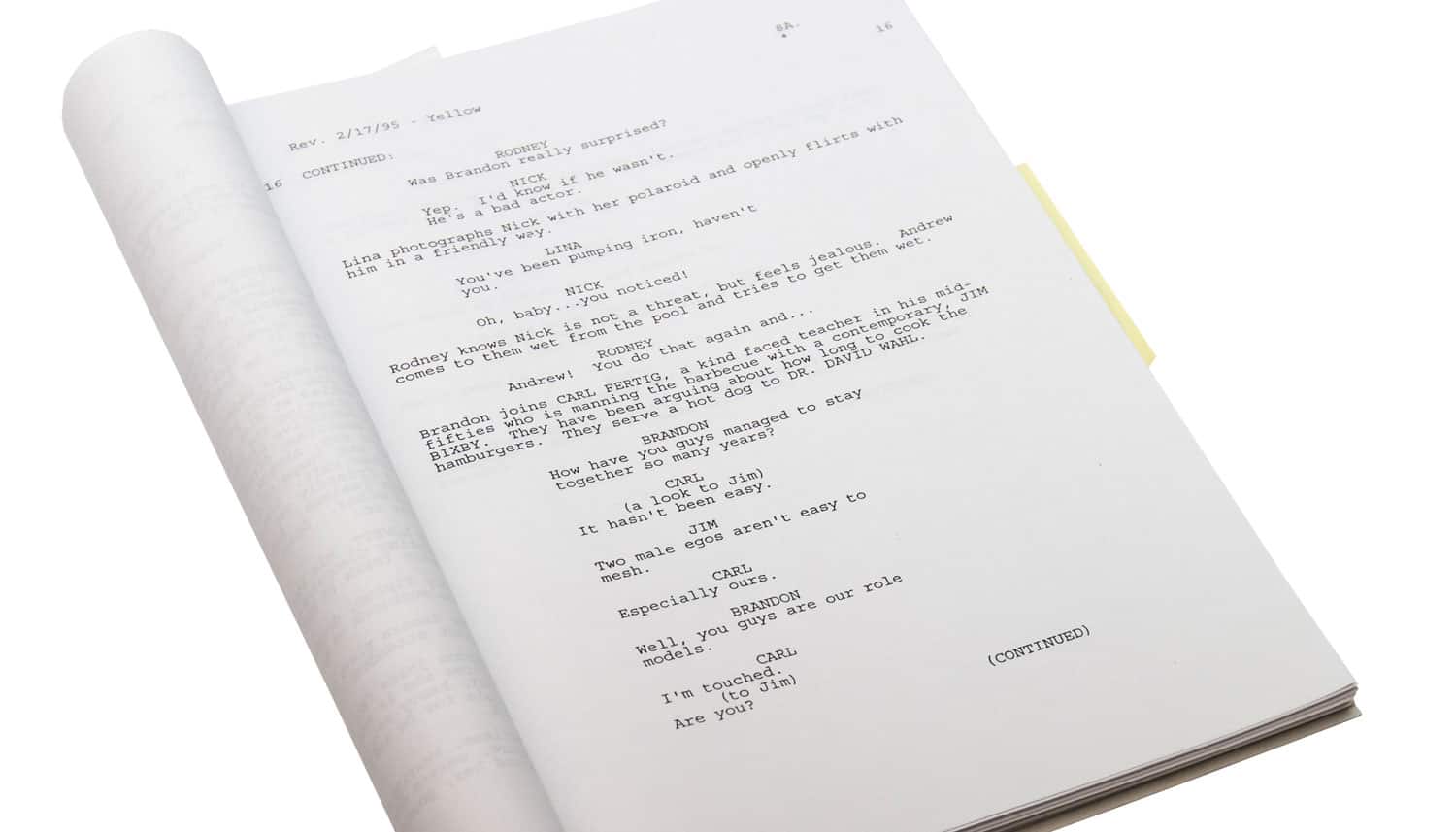

| The First DraftLearn how to properly write and format the first draft of your script. This module is a complete guide that walks you through every step of how to format a screenplay. |

| RewritingOnce the first draft of your script is ready, the real work begins. Learn what to look for in the rewriting process, how to identify problem areas that may adversely affect the story and how to get the most out of each plot, character and line of dialogue. Emmy-winning Executive Producer of “Everybody Loves Raymond,” Steve Skrovan, Writer/Producer Mike Emanuel, Writer John Anderson, Writer/Script Doctor David Freeman, Emmy-winning Director Jason Tomaric and Jerrol LeBaron, president of the script brokerage site, inktip.com share industry tips and techniques on how to effectively rewrite your script. |

| Marketing Your ScriptYou’ve finished the script, now what? Working Hollywood writers and producers take you through the process of finding an agent or manager. Should you approach a producer instead? How do you deal with the studio Hollywood Reader? How do you cope with rejection? This module takes you through the intricacies of the Hollywood system and how to manage it. |

This is by far, hands down, no questions asked, the best screenwriting course I have ever taken. I’ve finished my first script and have already gotten it in the hands of agents. Thank you, FilmSkills! – Eric C.