Welcome!

Hello, I’m Jason Tomaric, and welcome to FilmSkills. I’m a working director and cinematographer in Los Angeles, California and the founder of FilmSkills.

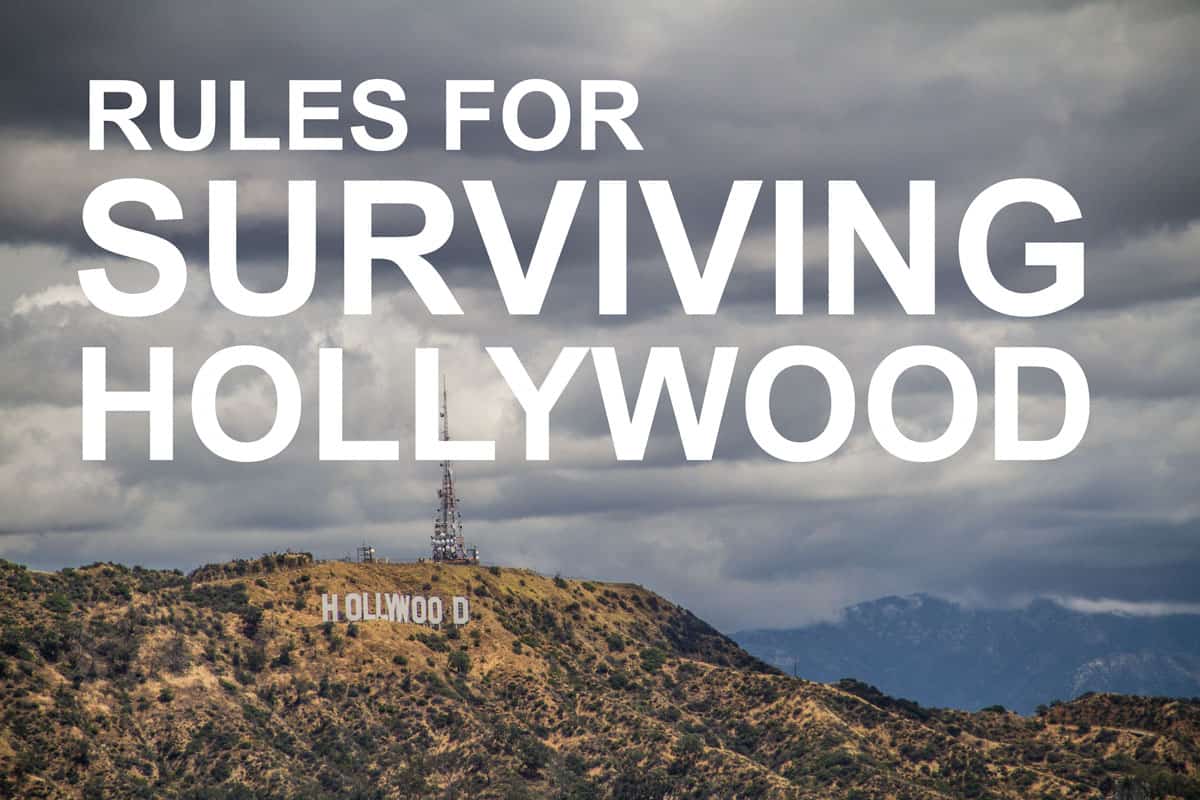

I can imagine we have a lot in common. I grew up in a small Ohio town and started a production company shooting local commercials for bike shops, restaurants, and attorneys. While I dreamt of shooting bigger projects in LA, I had no idea where to start. My family was a typical middle-income family with absolutely no industry connections, and film school wasn’t for me. But as fate would have it, our neighbors in the house behind us had a daughter, Johanna Jenson, who worked in the film industry in LA. Our neighbor would send Johanna newspaper clippings covering my film shoots, and after a while, Johanna and I became pen pals. I would ask her questions about her life working in Hollywood, then anxiously await her reply. She was a lifeline between me and my career dreams in LA. Her advice and kindness were instrumental in helping me move my career to the next level.

Eventually I moved to LA, where I built a successful career directing and shooting feature films, television commercials, and documentaries. If it wasn’t for Johanna’s kindness in helping an ambitious kid in Ohio, I may have never taken the plunge, and for that I am forever grateful.

As I continued to grow professionally, I was disappointed at the opportunities to learn– film schools were outrageously priced and had inexperienced – often bitter – instructors, books seemed too academic, and self-proclaimed experts on youTube were sharing what limited knowledge they had… from their bedroom studios and a webcam. I didn’t want any of that; I wanted to learn from the pros. And with that thought, FilmSkills was born.

Say Hello to FilmSkills

Johanna had a huge impact on my life and career. Afterall, it’s not every day that you can connect with a working Hollywood filmmaker. There isn’t a career day where you can follow around a director, producer, cinematographer, or editor like you can a police officer, doctor, or architect. Hollywood seems like a good old boys club where you have to know someone to get in, and once you’re in, no one on the outside matters. But I found the opposite to be true.

Hundreds of successful and talented filmmakers from all parts of the business partnered with me on FilmSkills to share their knowledge and experience with you. We take you step-by-step through the hard-learned lessons on how to build a career from scratch. FilmSkills is about real world knowledge from real world filmmakers.

“Film professors do not teach the real world. That’s why our instructors are working Hollywood filmmakers.”

Widely adopted

FilmSkills has quickly grown into the film industry’s largest film training site. Tens of thousands of students have learned from over 150 leading filmmakers. FilmSkills has also been widely adopted by over 70 film schools, including UCLA, Yale, NYU, Columbia College Chicago, and Full Sail. Why? Because at FilmSkills, you learn from the best people in the industry.

- James Cameron’s Assistant director team teaches you how to schedule and budget a film shoot

- Steven Spielberg’s producers teach you how to produce a film

- The directors of Castle, Star Trek, The X-Files, and The Fugitive teach you how to direct actors and the director’s craft

- Judd Apatow’s audio post-product team teaches you about ADR, sound effects editing, and Foley

- Emmy-Award winning Executive Producer of Everybody Loves Raymond and Seinfeld teaches you how to write a script

…and we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface. Our 150 instructors have won, or been nominated for, over 70 Emmy, Academy Awards, BAFTAs, and Golden Globes. I bet you can’t find a film school with that caliber of instructors, and at FilmSkills, they are all here for you.

Get the Jobs and Day Rate You Deserve

By the end of the day, you want one thing– to get the jobs you want and earn the paycheck you deserve. That is the core goal of FilmSkills. You will learn the process and techniques in the safety of your own home so when you get on set, you’ll have the edge. We are here to dramatically shorten your learning curve so you can accelerate your career. You may be wondering who am I to teach this?

I went from a film school drop out to earning $10,000/day as a director and cinematographer in Hollywood.

I went from directing local bike shop commercials in Ohio to an Emmy-winning career in LA earning a $10,000 day rate. I’ve shot documentaries that span 20 countries and TV commercial campaigns for major companies like Toyota, McDonald’s, and Microsoft. While my passion has always been filmmaking, a close second is teaching. I’ve seen a handful of people succeed in this business and hundreds fail. The ones who succeed all have some of the same traits– as do the people who fail. FilmSkills is about guiding you through the career minefield so you can improve your chances of being one of the success stories.

At FilmSkills, we’re not here to teach you the art. That’s your talent and gift. We are here to show you the tools, process, and industry techniques to harness and shape your creative vision into a career.

We’re so excited to have you with us and are ready to help you take your career to the next level. Let’s get started!