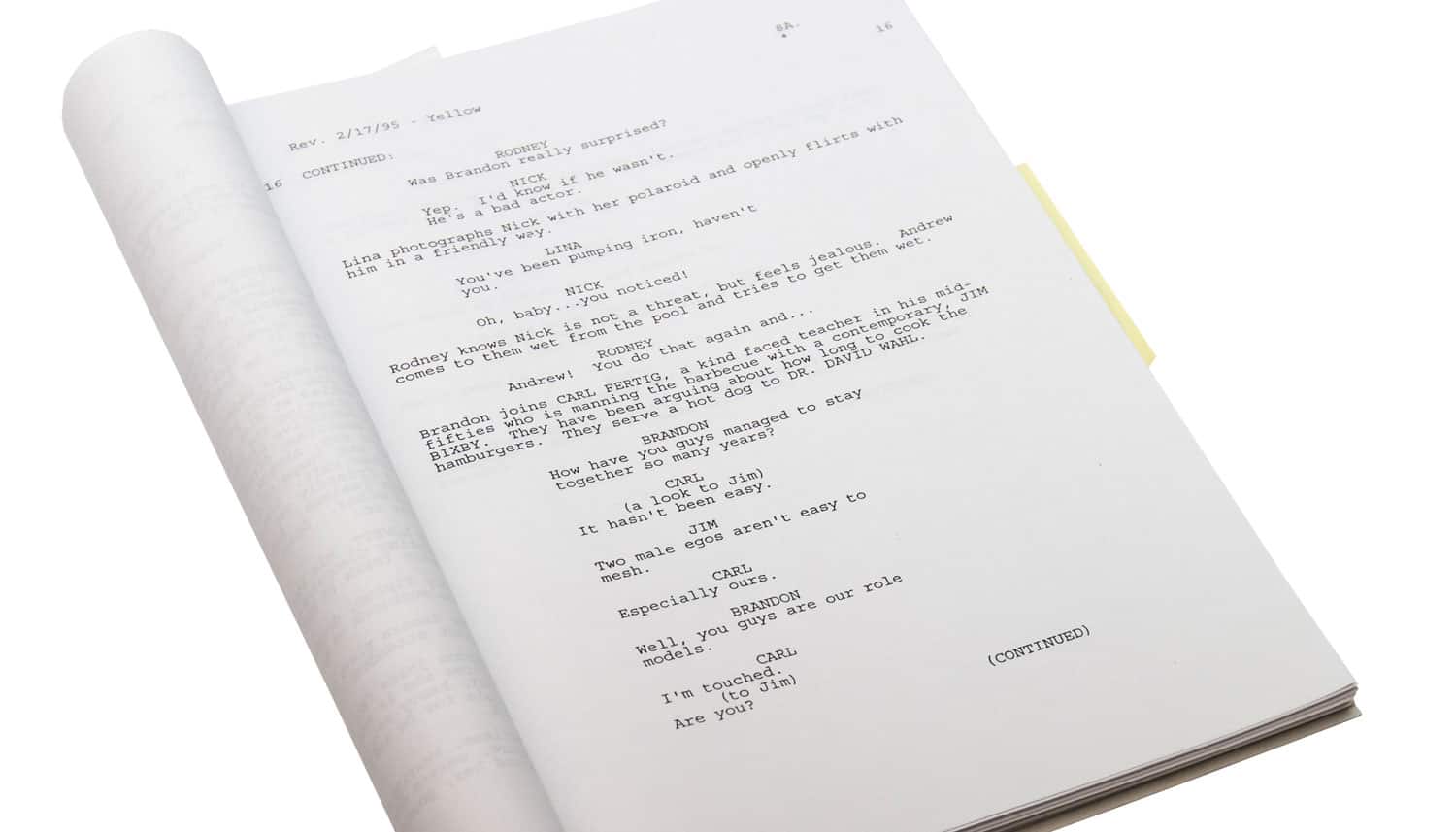

Believe it or not, the editing of a movie begins well before you shoot the first frame. Filmmaking is a tedious process of shooting a scene numerous times from many angles using only one camera, and it’s important to consider in pre-production, how these shots will be edited together. In the editing room, the editor assembles shots so the action in the scene appears to have had occurred only once, and was covered by multiple cameras positioned around the set. This can be tricky because the quality of the edit depends heavily on how well the footage was shot on location.

When on set, always shoot for the edit by envisioning how every shot will be cut together. A great way to ensure continuity between shots is for the actors to perform the scene in its entirety and cover as much of the scene as possible from each camera set-up. The more rehearsed the actors, the more consistent their performance from take to take; the more consistent the performance, the better the continuity of the footage.

Although editing is the process of assembling footage shot in the field into a meaningful, logical sequence, smart directors and cinematographers will determine how to edit the shots together before stepping foot on set. Shooting for the edit will help you better achieve your vision, control costs by eliminating extraneous set-ups and streamline the editing process.

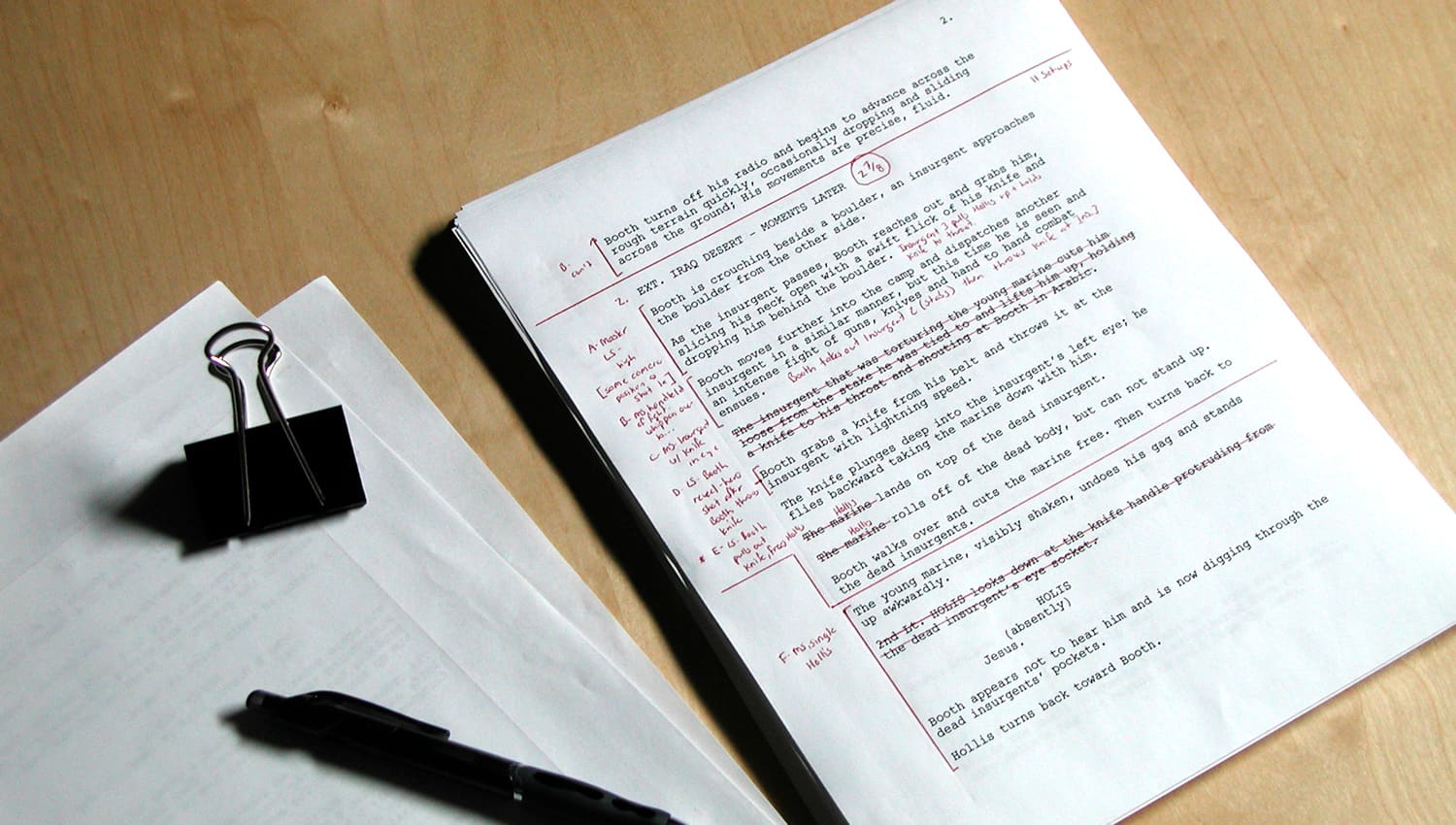

Shooting for the edit covers several aspects:

- Planning camera angles and movements – During pre-production, think about the relationship between each of the shots in the shot list and how they will ultimately cut together. Storyboarding the shots, or using software that allows you to animate each shot will help you visualize the flow the each scene.

- Plan to maximize the coverage in every camera set-up – If working on a tight budget, shooting each camera set-up from a wide shot, a medium shot and a close-up will instantly triple the options available to the editor.

One technique I employ when planning my camera angles is to place the camera where an observer would be compelled to look during a scene. As I block the actors, I take note of where my natural human tendency is to look. If I feel the need to look at a character’s face in a certain moment, odds are I will need to cover him in a close-up. If I am pulled to stand back and watch an entire action unfold, I will think about covering that part of the scene in a wide shot.

The camera is really an extension of the audience, so treat it as such. Pretend as though you were taking an audience member by the hand as the scene unfolds around you and walking him or her to different parts of the set to experience the action unfolding. What would be the best vantage point to see the action? Where would the audience member stand? How close or how far would he or she be? All these answers can translate directly into the positioning of the camera.